It’s all about how you sell yourself.

- Lack of empathy

- self-branding

- spectacle

- commodification

It's all about how you sell yourself, Image is everything

Jip Schalkx, 3315258

Research question: Are we fully aware of the market forces at play and the impact they have on our social interactions? I wonder how much young adults' and teenagers communication today is shaped by revenue-driven platforms and how commodification influences our social behavior.

From Jip Schalkx & the internet

Abstract

In a world shaped by hyper-capitalism, rapid technological change, and the constant demand for self-optimization, the boundaries between personal identity and marketable brand are increasingly blurred. This research explores how neoliberal ideals, social media platforms, and the rise of self- branding culture have redefined the way we live, communicate, and perceive success—particularly among young adults in the Netherlands today.

Drawing inspiration from Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (1967), I seek to connect his theory to the everyday experiences of 2024/2025, tracing how the spectacle manifests not just online but throughout our social and political lives. Through a mix of personal reflection, academic research, and cultural analysis, I untangle the forces that turn emotions, identities, and even time itself into commodities ready for consumption.

Rather than offering a definitive solution, this work invites the reader to pause, reflect, and reconsider: how much of who we are is truly ours, and how much has been shaped by forces we barely notice?

“Are we dehumanizing?” (thought)

The other day, I was walking The act of using legs for locomotion, typically with one foot in contact with the ground at all times with my friend on our way to the exhibition of Femke Herregraven. The sun was shining, which was so nice—and so needed. I miss the sun a lot, especially when it slowly becomes winter and the clouds create this concrete-gray wall above our heads. We stand still for a little while. I close my eyes and tilt my head up to the sky. It’s so nice...

Walking, on the hunt for coffee, Chaline asks me what my thesis is about. I find it hard to explain, but it might be good to talk about it with her. She recently graduated, creating a new online server where you can share data privately (pretty cool, if you ask me). I stumble trying to explain what I’m writing about.

“I want to talk about something that is happening now. I feel it around me, but I can’t quite put my finger on what it exactly is,” I say. “It’s about (hyper)capitalism but also about time. It’s about how we move as a society, how neoliberal we are here in the West—but also definitely the rapid technological changes, social media? This constant game of branding yourself... and how I feel like we’re all living in this really big, real-life theater play sometimes.”

“Are we dehumanizing?” I must sound like a lost doom thinker, putting it out like that.

But she agrees. There is something going on. She feels it as well. It’s hard to put into words, which is funny because the past few weeks, I’ve been hearing over and over in class how important language is—how you need to be able to describe yourself in this world to sell yourself. But what if I can’t explain what’s happening? Not yet, at least.

Introduction

This research paper is my attempt to untangle some of the strange, complicated forces shaping the Dutch society I live in right now. We’re living in a moment defined by hyper-capitalism, rapid technological changes, and this overwhelming push to always be optimizing ourselves. At the heart of it is self-branding—this idea that we need to turn who we are into something marketable, something sellable. It started with enterprise culture in the 1990s, but it’s been supercharged by social media, where your personality, skills, and even quirks become commodities.

What’s wild is how this isn’t just about making money or getting ahead anymore; it’s about becoming this curated version of yourself that feels almost like a brand or a product. Drawing on Guy Debord’s idea of the spectacle, I explore how everything gets turned into a performance, promising fulfillment that never quite delivers. Trends come and go at breakneck speed, leaving us constantly chasing, constantly consuming, but never fully satisfied.1

Are we fully aware of the market forces at play and the impact they have on our social interactions? — I wonder how much young adults' and teenagers' communication today is shaped by revenue-driven platforms and how commodification and branding influence our social behavior.

This paper isn’t about solving it all or purely critiqueing — it’s about trying to understand it. I want to explore how all these pieces fit together and figure out what’s really happening right now. It’s messy, contradictory, and hard to pin down, but through this process, I hope to bring some clarity to this moment I am living in.

In doing this, I take a leap back to where it all started—my first experiences online. Through this research paper, I explore what capitalism and neoliberalism actually mean and where they come from. I alternate between personal thoughts, questions, research, politics, pop-, enterprise-, and online culture—all through an artistic lens. Of course, this is just a glimpse; entire studies exist on every topic I touch on. But I have a deadline! If I had to take everything into account, I’d probably finish by the time I retire.

Maybe that’s also the strength of this paper—and of my work. It will never truly be finished because the world keeps evolving, and so will my research. I’m here to connect ideas, untangle topics I want to understand better, and lay them next to each other to see how they shape the way we move through the world. Because as a visual artist, photographer, designer—or whatever title fits—there’s a responsibility that comes with putting work out into the world.

It's all about how you sell yourself.

Are we fully aware of the market forces at play and the impact they have on our social interactions? Whether you’re a barista, therapist, or CEO, success today increasingly hinges on how well you package yourself—how effectively you craft an image, distill your identity into sharp, compelling snippets, and master the art of visibility. We live in a culture fueled by publicity, where performative social skills are valued over depth, and grabbing attention often matters more than substance.

The concept of the

ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas, beliefs and attitudes, consciously or unconsciously held,

which reflects or shapes understandings or misconceptions of the social and political world.

of

publicity

In marketing, publicity is the public visibility or awareness for any product, service,

person or organization.

(2002)2 feels more relevant than ever in an era where visibility is currency, according to Jodi Dean, an American political theorist and professor in political science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (NY). In short: it’s all about how you sell yourself.

But how did we get here?

The rise of the self-branded entrepreneur A person who sets up a business or businesses, taking on financial risks in the hope of profit. —the individual who turns their identity into a marketable asset—can be traced back to the 1990s and the emergence of enterprise culture A capitalist society in which taking on financial risks in the hope of profit is encouraged. . This model rebranded qualities like self-reliance, personal responsibility, boldness, and risk-taking as essential virtues for success, explains Paul DuGay, globalization professor at IOA.3 Framed as a path to self-improvement, happiness, and personal growth, it encouraged people to align their identities with capitalist ideals. The ultimate goal? To embody the entrepreneurial self, where fulfillment is measured by what can be monetized To change something into money, or to express something in terms of money or a currency. (Marwick, 2013).4

Social media took this further, creating platforms explicitly designed to amplify individuals. Instagram and TikTok assume there’s an audience for every moment. X (formerly Twitter) turns casual thoughts into viral content. Blogs once served as personal diaries shared with the world; vlogs simply adapted the format for YouTube’s ecosystem. Snapchat started as a way to share fleeting moments with close friends but quickly evolved into a tool for broadcasting daily life to a much wider audience.

Live streaming and vlogging, in particular, opened the door to massive exposure, allowing ordinary people to turn their personal content into careers. What’s striking is that this shift isn’t limited to celebrities or influencers—it’s happening to everyday people. A ten-year-old with a phone, a neighbor experimenting with TikTok, or a retiree sharing cooking videos—all can find themselves in the spotlight. With the right content and timing, anyone can achieve micro-celebrity A micro-celebrity is someone who achieves a modest level of fame or recognition, usually through social media or niche communities. Unlike big-name celebrities, micro-celebrities have smaller but dedicated followings in specific interest areas. They create content, interact with their audience, and build their personal brand around a particular niche or expertise. status, racking up thousands—sometimes millions—of views, likes, and comments.5

This culture of self-branding Self-branding is a strategic process aimed at creating, positioning, and maintaining a positive public perception of oneself by leveraging unique individual characteristics and presenting a differentiated narrative to a target audience. has become so embedded that many young adults see it as second nature: post a vlog, a photo, a tweet, and experience that fleeting moment of recognition. But this shift isn’t just personal—it’s systemic. Social media doesn’t just reflect our need for visibility; it actively shapes how we see success, attention, and self-worth. And in prioritizing the individual above all else, it reinforces a broader societal shift—one where presence and perception often matter more than reality itself.

R+R=Back

We live in a completely different digital zeitgeist than fifteen years ago. Back then, when I was about ten years old, I would send emails to my friends about nothing particularly special—just little messages letting them know I was thinking of them, boosting their ego by telling them Hvj Hou van jou / I love you and Wobsik, Wie ons breekt scheer ik kaal / Who comes in between us I’ll shave their head bold and asking when we’d chat on MSN. The kind of text I would write in those emails, or later on MSN, is what I see girls of the same age posting as comments under each other's Instagram photos. The only difference is that back then, those short conversations were one-on-one, and now they are public.

As digital platforms grew, so did their audiences. With MSN, you could create group chats. After came Hyves—the first Dutch platform where you could post photos, share thoughts, build profiles, and connect with followers. It introduced things like the “R+R = back” Reaction + Respect = Back trend, where leaving a reaction or showing respect by clicking a button became a social currency. Being on someone’s R+R list meant something—it gave you visibility and status. While this felt more public than MSN, it was still relatively contained compared to what we see now.

Raising questions

In a way, the essence of online destinations hasn’t completely changed. Platforms like Snapchat and TikTok, where users share quick, everyday moments, remind me of the emails I used to send. But the scale has shifted. The audience is bigger, the reach is wider, and the systems behind these platforms are profit-driven. Algorithms shape our interactions, prioritizing what’s most engaging—and that usually means that we will keep on scrolling and posting. What used to be a tool for personal connection has turned into a public, monetized space where even our smallest interactions are part of a larger system designed to keep us hooked.

This shift raises important questions about the role of social media. On one hand, it creates communities and lets people connect across the globe, building relationships and connections. But it also comes with downsides, especially for younger users. Research by the University of Amsterdam (Da Silva Pinho et al., 2024)6 shows that social media can negatively affect self-image, particularly for girls. It is also not just about what’s visible. There is a deeper biological pull to these platforms called the nucleus accumbens. For example, hearing a WhatsApp notification triggers dopamine release in the brain’s reward system. If we see that message as positive, the dopamine response increases, creating a sense of satisfaction. Over time, we start craving more of it, which makes stepping away from these platforms harder.

These topics often come up when discussing the effects of social media, especially its mental impact. But we don’t talk as much about the profit-driven systems behind the platforms we use every day.

Are we all turning into an entrepreneur?

While enterprise culture began as a business model, it has now woven itself into our social lives, politics, and even the way we speak. The rise of social media helped this enormously. Self-branding—strategically crafting an identity to be promoted and “sold” to others—has become a certain norm. We are encouraged to present ourselves as both authentic and marketable, blurring the lines between who we are and how we want to be perceived online and offline.

Our personal presentation, particularly online, is deeply influenced by advertising and marketing strategies rooted in neoliberal ideals. This has given rise to a new kind of entrepreneur: one who thrives on visibility, performance, and the constant act of self-promotion (Marwick, 2013).7 Let’s go back to the example of Snapchat and TikTok, where users share daily moments of their lives through short videos. With friends and followers spread across the globe, I understand the appeal of exchanging these small, everyday updates. But what could have sparked this culture of constant video sharing?

Vlogging took off in 2005 with the rise of YouTube, quickly becoming a mainstream phenomenon. One of the most popular formats involves documenting everyday life, where vloggers make an effort to be transparent and unfiltered. One reason it resonated so deeply with its watchers is the relatability—it creates a parasocial connection for the viewer—especially when they follow someone daily—leading them to feel as if they truly know the vlogger (De Bérail & Bungener, 2022).8

For those who grew up with vlogging as a normal way of sharing, where authenticity and influence are key, it makes sense that this facet of online culture would translate into how we communicate with one another. It’s no longer just content creators using vlogs to express their feelings and opinions—it’s everyone. For the generation born into this era, vlogging seems as natural as calling once was.

What I find interesting is that the practice stems from content creators who operate within a profitable revenue model. A revenue model is a framework for generating financial income. Behind these videos is a system designed for engagement, complete with public ratings like comments and likes. It makes me question how much the way young adults and teenagers communicate today is shaped by revenue-driven platforms or their mentality, and if we are fully aware of the market forces at play, and the impact they have on our social interactions?

Individual success as both reachable and expected;

The neoliberal subject

Have it all, be happy, fit, and fulfilled

Okay, let’s take a step back. Since self-branding and commodification will come up often in this paper, it’s worth unpacking what neoliberalism actually is. Because it is inescapable—influencing nearly every aspect of our current society in the West. Marwick lays this out clearly in her book, Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Self-Branding in Web 2.0.

Neoliberalism is a term that has shifted in meaning over time, shaped by different economic and political moments. It first emerged after World War II through economists of the German Freiburg School—Rüstow, Eucken, Röpke, and Müller-Armack—who sought to update classical liberalism. Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, economic freedom, political freedom and freedom of speech. Their version of neoliberalism wasn’t about unchecked free markets but about striking a balance—protecting competition while ensuring social responsibility. Unlike hardline free-market advocates, they saw monopolies and cartels as threats to genuine economic freedom. They argued that markets needed structure, a framework that kept them fair and accessible rather than ruled by the most powerful players (Boas and Gans-Morse, 2009).9

But over time, this careful balancing act faded. Neoliberalism evolved into something much broader, moving beyond its original economic framework. It became the driving force behind global economic restructuring, pushed forward by institutions like the IMF The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. and World Bank. By the 1980s and into the 2000s, it had transformed into a dominant ideology—one that championed free markets and individual entrepreneurship, often at the expense of social protections and public welfare (Harvey, 2007).10 What started as an effort to balance free markets with social responsibility has now turned into something much bigger—an ideology that shapes not just economics, but how we see ourselves, how we relate to others, and even what we find beautiful or valuable. This shift wasn’t just about policy changes; it signaled a deeper transformation in how societies functioned, placing competition and self-reliance at the core of everyday life.

I must because I can

In recent years, the term “neoliberalism” has taken on a life of its own, often used as a catch-all phrase to critique anything associated with free-market A free market is one where the laws of supply and demand provide the sole basis for the economic system, without government intervention. policies. It’s become so broad it can “mean virtually anything… as long as it refers to normatively negative phenomena associated with free markets”11 mentions T. C. Boas, Professor of Political Science at Boston University and J. Gans-Morse associate Professor of Political Science at Northwestern Universit.

Today, it’s not just about economic policies—it’s also used to describe wider cultural, social, and political shifts. Neoliberalism has become a kind of “lens” through which academics analyze everything from politics and kinfolk to literature and education (Seiler, 2009).12

In a neoliberal society, market principles don’t stay confined to the economy; they bleed into personal relationships and social life. Marriage, family, even friendships start to reflect a “market logic,” where everything is understood through a lens of discipline, efficiency, and competition (Marwick, 2013).13 This creates what’s often referred to as the “neoliberal subject”—individuals who are self-regulating, entrepreneurial, and constantly optimizing themselves as Foucault argued.

'Neoliberalism offers its subjects imaginary injunctions to develop our creative potential and cultivate our individuality, injunctions supported by capitalism’s provision of the ever-new experiences and accessories we use to perform this self-fashioning- I must be fit; I must be stylish; I must realize my dreams. I must because I can- everyone winds. If I don’t, not only am I a loser, but I am not a persona at all; I am not part of everyone. Neoliberal subjects are expected to, enjoined to have a good time, have it all, be happy, fit, and fulfilled’ Dean, 200814

Neo-libralism 🤝 capitalism

This subject, shaped by neoliberal ideals, is expected to be enterprising, self-regulating, adaptable and entrepreneurial—embodying the image of the rational “homo economicus” who thoughtfully weighs risks and rewards. But as Jodi Dean (and even Foucault, Debord and Harvey) point out, this vision is imaginary, not a reality. Neoliberalism pressures individuals to “develop our creative potential and cultivate our individuality,” while capitalism provides endless consumer experiences to support this self-fashioning. The neoliberal subject, then, is compelled to perform success and individuality, often for approval and validation within a market-based system.15

This relentless need to pitch ourselves not only fragments our communication but can also erode a stable sense of self. Media and popular culture further reinforce this neoliberal subjectivity often in ways that go unnoticed. Anna McCarthy, Professor in the Department of Cinema Studies NYU, for instance argues that reality TV serves not only as entertainment but also as a vehicle for teaching “the government of the self” as she calls it. Inspiring viewers with norms of citizenship and personal management.

Programs like The Kardashians and Big Brother-style series promote self-discipline, fashioning a professional, middle- and upper-class aesthetic as an ideal to aspire to. Meanwhile, self-help books, lifestyle magazines, and films like The Devil Wears Prada and The Wolf of Wall Street spread the same message—suggesting that personal hardships can be conquered through hard work and self-determination, framing individual success as both attainable and expected (McCarthy 2007, 17). Social media platforms like TikTok reinforce this narrative, with influencers promoting luxurious, seemingly effortless lifestyles. They present the idea that with enough dedication and hustle, anyone can achieve financial freedom and aesthetic success. However, this portrayal frequently stands far from the realities of most viewers, blurring the line between aspiration and illusion.

Social media; a self-fulfilling prophecy

Another major influence on neoliberal subjectivity is the trend of self-branding, which encourages individuals to align their identities with market demands, becoming “ideal” commodities by embodying traits that they believe employers or viewers want. Critics argue that this form of self-branding reflects the “market colonization” of personal identity, as people adapt their behaviors and values to align with economic expectations. This mindset goes hand in hand with the bandwagon effect, a well-known social and political phenomenon: when people are faced with a decision—whether in elections or everyday life—they often side with whoever appears to be winning. The more something is seen as popular, the more people are drawn to it, reinforcing its status (Davis & Harless, 1996).16 Social media amplifies this effect, shaping what we consider relevant, desirable, or even true.

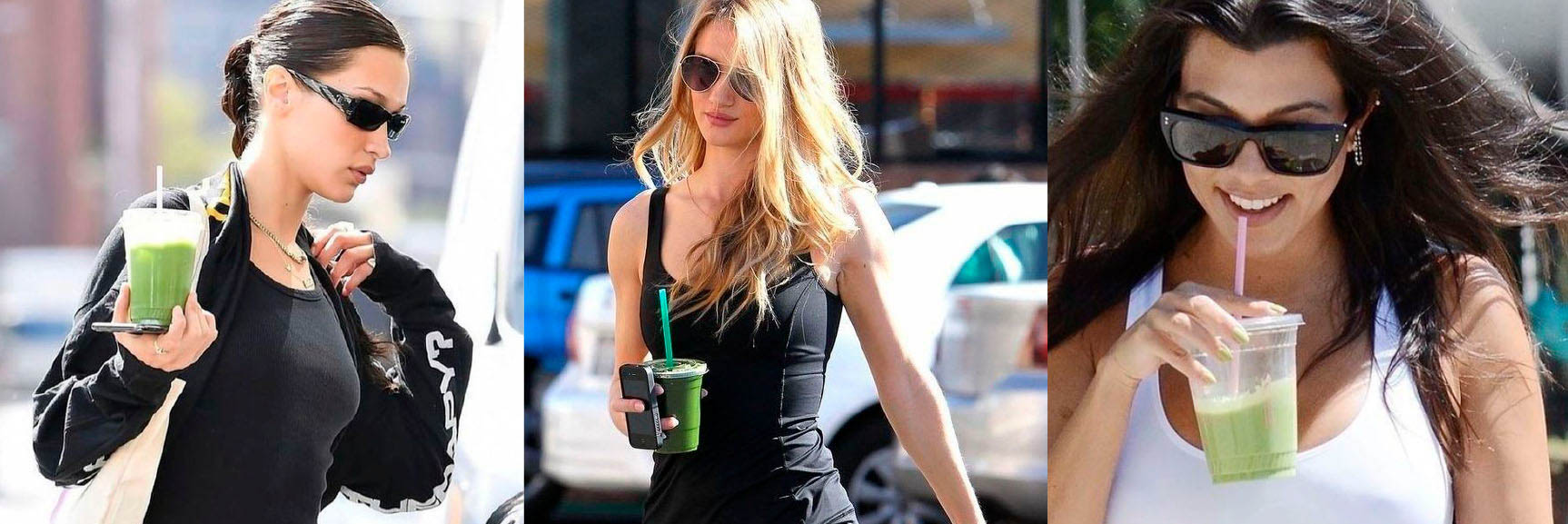

Charlotte Rohdes, artist, writer, and type designer, illustrates this well in her book ‘You Loved an Image (2024)’.17 She takes Kim Kardashian—queen of Instagram, ruler of the image-driven world— as an example. Kim K doesn’t just follow trends; she defines them. And with that power comes influence, but also responsibility. Kim K, for instance, has played a major role in popularizing the Brazilian butt lift globally, statistically one of the riskiest plastic surgeries. Her followers, eager to embody the same ideal, take on these dangers to pursue a body that fits the moment’s beauty standard.

Social media platforms act as self-fulfilling prophecies. If an account already has a massive following, it’s seen as important—making it even more likely to gain attention. The more something is shared and repeated, the more legitimate it appears. This is how certain ideals, such as what it means to be a “desirable” woman, are created and reinforced. The body becomes an asset—something to be modified, invested in, and marketed. Kim K, in this sense, is both the creator and the product of the bandwagon effect in femininity, writes Rohdes.18

When we are drawn to something—whether it’s a lip gloss, a hoodie, or an aesthetic—we want to adopt it as part of our identity. These objects signal status, taste, perfection, validation, or belonging. We reblog, repost and if we can afford it, we buy into it. Kim K’s Skims and Kylie Jenner’s lip kits are all part of the same cycle.

But what happens when the trendsetter moves on? Recently, rumors surfaced that Kim had quietly reversed her BBL just as body ideals began shifting. Similarly, Kylie Jenner appears to be rebranding her look. This leaves their followers in limbo, having invested in an aesthetic that is no longer relevant. BBLs are expensive, and for many, this investment no longer pays off. But no one warns teenage girls that beauty standards have such a price and expiration date.

This phenomenon isn’t new explains Rodhes. In The Selfish Gene (1976), Richard Dawkins introduced the concept of memes—not in the internet sense, but as cultural ideas that spread through imitation. The word meme itself comes from the Greek word for imitation, and according to Dawkins, a meme’s success depends on how well it serves its host. Social media accelerates this process, determining what gains traction, what becomes desirable, and ultimately, what is accepted as common sense. The more something is repeated, the more natural it seems. And before we realize it, our perception of what is normal, aspirational, and worth striving for has been reshaped.19

Self-branding: It’s not just a practice, it’s a mindset

Self-branding took off with the rise of project-based work cultures, entrepreneurial thinking, and the gradual mainstreaming of the internet. It became popular across industries during the 2008 economic recession, a time when standing out was needed because of the economic fluctuation. At its core — self-branding means applying marketing strategies to yourself, turning personal traits into commodities to catch the attention of employers, clients, or an audience. It’s not just about practice; it’s a mindset.

That mindset stems from enterprise culture, which glorifies the “go-getter” attitude of the free market, framing it as more than just an economic approach (Marwick, 2013).20 It’s presented as a moral ideal. It might not come as a surprise because it pairs perfectly with the self-help industry, where constant self-improvement is sold as the ultimate solution for navigating social and economic instability (McGee, 2005).21 You know the drill: books, webinars, tutorials, even memes—all teaching you how to refine yourself into the most attractive, marketable version of ‘you'.

'Within any industry, corporation, or profession, the aspirant reaches the economic apex when she becomes a celebrity, a human icon. Now colleagues cite her name with awe or jealousy when she is not present; subordinates show deference as a matter of course; her ideas are respected by the very fact that they arose from her; even to meet her is an honor; and all long to hire her, work with her, and gain her counsel, were she only available. Now lifted above the usual competitive anonymity, the performer can use her hard-won iconicity to assert advantages over competitors and to command for her services a market premium’ Sternberg, 199823

But self-branding has grown into more than just a tool for career advancement. It’s now about cultivating a kind of celebrity-like status, where your most appealing traits—whether that’s a talent, a skill, or simply your personality—are carefully curated, amplified, and sold. These attributes are no longer just personal qualities; they’re assets, measured by their ability to draw attention and generate value.

In a world shaped by social media, there’s an ever-present demand to develop the right skills to stand out. If you don’t? Well, the unspoken message is that maybe you’re just not extraordinary enough to matter. It’s this relentless need for validation and performance that pushes us into viewing ourselves as commodities, with our worth tied to our marketability.22

The endless elevator pitch

With social media surrounding us at all times and the pervasive neoliberal free-market mindset, personal branding has become an integral part of daily life. It’s no longer just about professional settings; you’re expected to always have your story ready, know what you stand for, and sell yourself effortlessly. But what happens when this mindset starts influencing how we navigate everyday situations—whether we’re spending time with friends, at school, or working a regular job? The pressure to maintain a 'brand' seems inescapable.

Platforms like Instagram and TikTok dominate the social media landscape, offering a space where visibility, likes, and connections can be achieved in the blink of an eye. Millions of users churn out these micro-moments daily, turning life into the equivalent of an endless elevator pitch—a fleeting opportunity for a burst of recognition.

The elevator pitch concept originally came from the US business world, where entrepreneurs would seize the chance to pitch their ideas to investors in the short duration of an elevator ride—about 30 seconds. The goal was to deliver a clear, compelling message that could spark collaboration or sell a vision.

Social media now applies similar constraints, transforming communication into a performance. TikTok gives you just 60 seconds to leave a mark.24 Platforms like X (formerly Twitter) restrict you to 280 characters.25 These limitations demand immediacy and impact, prioritizing attention-grabbing content over meaningful connection. The result? Everyday interactions increasingly resemble polished, performative acts designed to compete in a crowded digital marketplace.

A halfway conclusion

I wonder to what extent this way of interacting with each other online seeps into our daily lives. If we have grown so accustomed to the star-like allure of our online personas and to always striving for more, better, and faster to stand out, what kind of impact does that have on the empathy we show one another, especially within the social groups in our daily lives?

At times it feels as if our online personas and real-life selves have become so intertwined that we’re now living in a new world, one where we create a new identity based on how we behave and want to be perceived online, and how we interact with each other in that space. It’s a world shaped by a more individualistic mindset compared to fifteen years ago.

Image is everything

”I wonder how much young adults and teenagers communication today is shaped by revenue-driven platforms and how commodification influences our social behavior.”

Hey, how are you? (thought)

Charley was visiting from London, so we met up for pizza with some friends. You know how it goes—yappa yappa yappa.

Earlier that day Alice ran into Ray, Thijs, and Julia—three in a row!

Jip: “Those are the good ones.”

We share a lot of mutual friends, and these are solid friends. There’s no better feeling than spontaneously bumping into people you love. Half-friends and quarter-friends are nice too, but the urge to stop and chat fades, especially if you’re in a rush. And here, people are always in a rush…

Alice: “Do you always say hi?”

Me: “I try to. Or at least smile. Sometimes I’m not in the mood, but most of the time, I want to know how they’re doing.”

Jip wasn’t having it.

“That ‘Hi, how are you?’ thing feels so empty,” she said. “People ask, but they don’t follow up. They’re in a hurry, or they don’t really know you. So why even ask? What’s the point of the endless ‘Hi, how are you?’‘ I’m good, and you?’ ‘Yeah, good.’ ‘Bye.’ It’s fake. Things aren’t always good, and I don’t want to pretend they are. So just don’t ask if you don’t really care.”

She had a point.

The habit of greeting people with “Hey, how are you?” feels more like a reflex than a question. A placeholder for something that once had meaning. Combined with our rushed mentality, and always being on the go, it sometimes feels hollow.

But maybe that’s just how things work now—quick check-ins, brief exchanges, everyone moving at their own pace. Maybe that’s okay. But still, I wonder what would happen if we broke the rhythm now and then. If we answered honestly. If we actually listened to those half- and quarter friends. Would it feel awkward? Or would it remind us that small talk doesn’t have to be empty?

Thought

What is truth, anyway? Truth has many faces—

who says what, who believes what,

what do you know, where do you come from?

Truth has shifted meaning over the years.

As a child I believed my mom

or the eight o'clock news my dad watched every night—

they'd tell me the truth.

Or newspapers, the ones with proper sources.

Magazines wouldn’t tell you the truth

just a very nice version of it.

Then there is the internet,

YouTube, Google Scholar, Wikipedia.

Wikipedia, truth with a grain of salt,

at least, that’s what my teachers would say.

We have access to so many truths—

we might confuse the truth with our opinions.

Or do our opinions become the truth?

Because everybody is so opinionated nowadays.

Right?

So, mine doesn’t need to be added to the pile.

But here I am,

quite opinionated myself as well.

When I realized the news isn’t always objective

but simply someone's version,

I felt betrayed.

Maybe it was naive to believe in an honest source at all.

Is it foolish to want that?

Because it gets harder to pin down what truth even means,

or which truth I want to believe.

Should we trust in social media or the internet.

Truths mingle there, AI shapes them,

tailored to fit me.

Left, right, screaming at each other.

Which one should I pick?

The endless loop of star allure

In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord describes already in 1967 a world where ideology A system of ideas and ideals, especially one which forms the basis of economic or political theory and policy. doesn’t just influence reality—it replaces it. A world where people are pulled away from real life and immersed in a carefully constructed universe of appearances. Decades later, it sometimes feels like we’re living in the exact spectacle he predicted, except now it’s faster, shinier, and algorithmically optimized. I explore the connection between Debord’s theory and the way we move through daily life now—in 2025. His ideas form one of the foundations of this research because if anything proves their relevance today, it’s our obsession with self-branding, the commodification Commodity; A raw material or primary agricultural product that can be bought and sold, such as copper or coffee. commodification of identity, and the way consumer goods shape our sense of self-worth.

As Debord wrote, we’re surrounded by a constant stream of images and messages, where even our thoughts and emotions start to feel like something to be consumed. It’s not so much about what things are anymore, but about what they represent. A coffee isn’t just a drink—it’s a lifestyle, a mood, a moment you might share online. The way we in the West (or more specifically, in the Netherlands) commodify our identities and let consumer goods define our value makes it feel like we’re living in ideological echo chambers An echo chamber is "an environment where a person only encounters information or opinions that reflect and reinforce their own." The term is a metaphor based on an acoustic echo chamber, in which sounds reverberate in a hollow enclosure. —not just online, but in the physical world too. It’s subtle but powerful—this sense of moving through carefully staged realities, where meaning is filtered through aesthetics and performance.

Debord warned that the spectacle turns people into passive spectators of their own lives. And sometimes, social media does seem to amplify that. Instead of simply being, we curate, edit, and brand ourselves. Every experience is pre-framed through how it might be perceived. Consumerism The belief that excessive consumption of goods has a positive effect on the economy and that companies should create goods and services that consumers most desire plays into this too—it’s no longer about what we own, but what those things say about us. Apple doesn’t just sell phones; it sells status. Louis Vuitton isn’t about bags; it’s about belonging to an exclusive world. The spectacle convinces us that fulfillment isn’t found in real connection, but in consuming the right things. And we fall for it, over and over again.

This cycle isn’t just personal—it’s political. Political campaigns now function like commercial brands. Candidates are marketed like luxury products. The rise of populist leaders in Europe and the United States has been fueled by the same spectacle logic that drives mass consumer culture. Sensationalism, viral moments, and image often outweigh actual substance or policy. And while social media claims to connect us, it also deepens division—reducing political conversation to aesthetic outrage rather than real dialogue.

Debord also critiques how modern society turns time itself into a commodity—something to be bought, sold, and controlled. He describes pseudo-cyclical time: as time reshaped by industry, where work, leisure, and even politics are blended into something consumable. In this world, even time is repackaged and resold. As Debord writes, “A product that already exists in a form suitable for consumption may nevertheless serve as raw material for some other product.”26 Our time, once restructured to meet the needs of capital, is then fed back to us in the form of endless trends, distractions, and content.

His warning about false interaction and deepening isolation feels increasingly relevant today. We’re more visible than ever, yet often disconnected from meaningful experience. I spoke to a group of girls aged twelve to fifteen, and they described moments when this paradox showed up in their lives. One example stood out: a fight had broken out in their class—but only online. In real life, no one talked about it. Both realities existed side by side for weeks until it was finally addressed in person. That separation—between digital and physical—had made it almost invisible.

In today’s hyper-mediated world, we move through a polished playground of perfection, where it’s easy to believe that what we see online reflects what most people think. If you encounter the same ideas again and again, they must be the majority view, right? But stepping outside these digital echo chambers—where images, ideas, and emotions are carefully filtered—is becoming more difficult.

What strikes me

One of the most striking changes today is the decline of third places—cafés, parks, libraries, and community centers that once served as social centers. Economic pressures, urban policies, digitization, and shifting lifestyles are causing many of these spaces to disappear, often replaced by generic franchises that not only dominate the physical space but also flood our online timelines with advertising. Small local shops that once fostered neighborhood connections have largely given way to supermarkets and online shopping, reducing casual social interactions. Even these spaces are now designed for efficiency, with self-checkout stations minimizing human contact.27

At the same time, social media promises connection, yet studies show that increased engagement often leads to greater loneliness. That’s not to say social media is inherently bad—it fosters global connections and opportunities, something I’ve experienced myself. But its constant stream of curated realities, doomscrolling, and image bombardment can be isolating. This trend extends to urban design, where convenience often takes priority over community. Gated communities, high-rise apartments, and commercial districts with little pedestrian space make spontaneous social encounters rare—especially between people from different backgrounds.

Despite being more digitally connected than ever, younger generations report rising loneliness and mental health struggles. The social pressure from online interactions fuels anxiety and withdrawal from real-world relationships. Even in shared physical spaces, people are often emotionally distant, more engaged with their screens than with those around them.

'The Web makes the case for branding more directly than any packaged good or consumer product ever could. Here's what the Web says: Anyone can have a Web site. And today, because anyone can ... anyone does! So how do you know which sites are worth visiting, which sites to bookmark, and which sites are worth going to more than once? The answer: is branding. The sites you go back to are the sites you trust. They're the sites where the brand name tells you that the visit will be worth your time—again and again. The brand is a promise of the value you'll receive' Peters, 199728

Echo chambers

This insight feels even more relevant in today’s age of algorithms, where social media delivers an overwhelming flood of information, curated for us every day. Based on our browsing history, the photos we like, the shops we visit, the recipes we search for, or even how long we pause on a video, algorithms shape the digital worlds we inhabit. Companies like Meta build extensive data profiles to define our supposed interests and sell this information to advertisers (Jansen, 2025).29 But do these profiles truly represent who we are, or are they a distorted reflection of an increasingly blurred boundary between our human and online lives?

The internet now plays an undeniable role in shaping our identities. We believe we’re in control of what we search for and explore online, but in reality, much of it is decided for us (Jansen, 2025).30 Algorithms deliver a tailored experience where we no longer actively search for content; instead, it is handed to us in a neatly curated package, with options so close to our preferences that we rarely feel the need to step outside our algorithmic bubbles. After all, why search when 99% of the choices already suit your tastes?

Made-to-measure #algorithms

This tailored experience, while convenient, has profound implications. Every click we make online generates profit for someone else, and everything we see is something chosen for us rather than discovered (Jansen, 2025).31 This raises questions about how we make daily decisions and what it means for the world we live in. Are we still capable of forming independent opinions, or are our choices increasingly shaped by algorithms designed to maximize engagement on social media?

We are so intensely focused on ourselves that the gap between us and people with different perspectives is widening, further amplified by algorithms curating what we see based on our preferences and likes. This creates echo chambers, where our existing beliefs are constantly reinforced, making it harder to challenge our own views or understand those of others. Those echo chambers limit exposure to diverse viewpoints which imply meaningful dialogue across different backgrounds and ideologies.32 Several sources underline the idea that social media algorithms therefore contribute significantly to reduced empathy and increased polarization in society. By feeding us content that aligns with our preferences, they strengthen confirmation bias and intensify political divides. Moreover, the constant exposure to curated feeds of like-minded opinions discourages critical thinking and nuanced discussion. Over time, this dynamic destroys the collective capacity for mutual understanding, isolating us in our curated realities. As a result, we’re losing not just empathy, but also the ability to genuinely connect or engage with perspectives outside our own.33

The impact of these echo chambers extends far beyond individual experiences, shaping how we communicate, perceive others, consume news, and even vote. For instance, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Donald Trump’s campaign ran over 160,000 different types of ads per day, each micro-targeted to influence specific groups with tailored messages like calls for a border wall, a pipeline, or the slogan “Make America Great Again.”34 This level of targeting raises critical questions about the fairness of elections. Are voters’ decisions truly their own, or are they heavily influenced by the tailored content they consume, thinking it reflects their independent opinions?

The reality is likely a combination of both. Algorithms don’t create our beliefs from scratch, but they amplify events and experiences already present in our lives, coloring our social profiles and subtly shaping how we perceive the world. As we increasingly live in these curated realities, the line between our own thoughts and the influence of algorithmic design becomes harder to discern, leaving us to navigate an internet that profits from shaping not just what we see, but also who we are.

The economy has distanced itself from meeting human needs

At Femke Herregraven's exhibition ‘Dialect’ I feel her work guides me through my questions, gradually becoming clearer as I move through the space. The show investigates vocalization experiments through a mixed-media installation. Located in an old water reservoir, visitors descend into a dark, circular basement to view the work. The space has organic walls, and small spotlights highlight different objects, creating a pathway to follow. Upon entering, soft sounds and small sculptures—roughly the size of your arm—lead you toward a large 3D video projected on the wall. The video shows the exact basin you are standing in being filled with water and overgrown by nature while various tones play, blending perfectly with the environment to create an immersive experience. Further along, in a narrow corridor, you encounter an AI-rendered video accompanied by sounds inspired by an unknown language and the atmosphere of a hospital and some crazy cats.

It’s not necessarily this installation I want to talk about but more the research behind her projects. Herregraven has spent over ten years researching financial technologies, infrastructures, and value systems. Her work explores how these abstract structures influence landscapes, ecosystems, individual lives, and historical narratives.

The modern financial system is immense and arguably one of the most influential forces in our daily lives. Coupled with advancing technology, it plays a central role in shaping the world. Large manufacturing companies rely heavily on credit, embedding finance deeply into nearly every aspect of the economy.35

Herregraven’s work highlights how this sector has become so dominant that almost everything now revolves around profitability in modern life. It’s no longer just about money; it’s about risk, speculation, and endless growth. By combining her research and mixed-media installations she brings the paradox to the surface: we know resources are finite, yet capitalism’s engine demands infinite expansion. It’s a system that thrives on creating risks—environmental, social, economic—while simultaneously profiting from them. The economy has distanced itself from meeting human needs. This creates a system where the production of wealth is intrinsically tied to the creation of risk turning it into a system that not only generates insecurity but also profits from them.

As Guy Debord described in The Society of the Spectacle, everything today has been commodified. Artist and researcher Femke Herregraven confirms this in her work, showing how, under neoliberalism and the free market, both people and ecological systems are reduced to mobile assets—traded, relocated, and exploited in the pursuit of economic growth. This often happens without regard for their intrinsic ties to specific places. Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing further connects economics and ecology through the history of wealth concentration, where humans and other living beings are treated as investment assets, detached from their original environments.

This, as Herregraven points out, is a form of slow violence—subtle, often invisible, but deeply impactful. It restructures both natural and social systems for economic gain while remaining hidden from those benefiting from the spectacle.

The avocado trend

Think back to the avocado trend. A few years ago, it was everywhere—on brunch plates, smoothie bowls, t-shirts, socks, notebooks, in art and magazines. Bella Hadid drinking an avocado smoothie popped up on your feed, Nic Kaufmann posted a video doing an avocado face mask with his girlfriend. It all seemed innocent enough—just people enjoying their day. But being pushed by the algorithm, behind these millions of views, companies saw oppertunities. And the next time you crave a smoothie, you might subconsciously reach for the avocado flavor—why not, right?

You could say a similar dynamic is at play in the rise of social media figures like Andrew Tate, whose content floods the feeds of young men. Tate, a self-proclaimed entrepreneur and former kickboxer, has gained massive popularity by promoting a hyper-masculine, Hypermasculinity is a psychological and sociological term for the exaggeration of male stereotypical behavior, such as an emphasis on physical strength, aggression, and human male sexuality. materialistic lifestyle centered on financial success, dominance, and control. His videos, filled with luxury cars, expensive watches, and advice on "how to be a real man," have become part of the algorithm-driven content young audiences consume daily.36 Just as the avocado trend subtly influenced consumer choices, Tate’s messaging is shaping how young men perceive success, money, and relationships.

What’s invisible in all of this, though, is a harsh reality elsewhere. Take Chile, for example, where large-scale avocado farming is contributing to the strain on already limited water resources.37 The growing demand for avocados in the West has intensified pressure on local water supplies.38 In some areas, rivers have dried up, leaving communities without access to the water they once relied on.

Next to that, the unhampered influence of figures like Andrew Tate is having real-world consequences. His rhetoric—centering on dominance over women and an extreme focus on wealth—reinforces outdated gender roles and fuels misogynistic attitudes in the mindset of young men. The promise of luxury and power may seem aspirational, but it risks shaping a generation of young men who view relationships through the lens of transaction and status rather than mutual respect.39 Just like the avocado trend, these ideas don’t exist in a vacuum. They are marketed, consumed, and over time, absorbed into our way of thinking—often without us even realizing it.

When the ad comes first, then the product #Political episode

In the radio show Spijkers Met Koppen, writer, and actress Van Zelm expressed her confusion about the bizarre rise of personal branding in politics—and honestly, she nailed it. Politicians now treat their appearance and social media presence as part of their “brand,” shaping not just their image, but also their views and proposals around it. A parallel with the commercial world emerged when Holland's Next Top Model winner Loiza Lamers explained that a model today has to fully embody a brand: “A model breathes and lives that brand—not just during photoshoots, but also online and through their outfits.”40

This branding mindset seems to have fully infiltrated politics. VVD party leader Dilan Yesilgöz recently posted an Instagram tour titled Dilan’s Room Tour, complete with a photo of an Armenian woman holding a Kalashnikov—seemingly referencing themes of war and national security. Was this meant to signal her political goals, like promoting stability and defense? “Typical VVD themes,” Van Zelm noted. She also pointed out the Dolly Parton quote coasters on Yesilgöz’s desk, sarcastically dubbing her a true "#girlboss"—just with a twist of everything.

Today’s politicians often seem more focused on broadcasting than listening, turning public debate into a curated performance. When PVV Minister of Asylum and Migration Marjolein Faber was asked whether she ever reflects on her actions, she dismissed the question by saying she’s not part of the “thought police,” so she keeps her thoughts to herself.

This shift begs a bigger question: when personal branding starts shaping political decisions and crisis responses, where do we draw the line? Van Zelm notes how even serious proposals like the Distribution Act—meant to address the refugee crisis—are used more like marketing tools. Meanwhile, the situation at Dutch asylum centers continues to deteriorate. During a recent debate, Faber was shown a letter from GGD doctors detailing cases of malnourished children in a shelter in Assen, where kids had to pee in buckets and were too afraid to play outside.41 Her response? “I can’t imagine that, because food is provided. The bed, bath, and bread arrangement is there.” She closed with a chilling remark: “If things are so poorly organized here, then why do so many people still come?”

It’s starting to feel like Dutch politics mirrors the commercial world: the ad comes first, and only then do we think about the product. Politicians focus on labeling each other—“climate leftist” vs. “radical right representatives”—instead of working toward actual solutions. The bigger concern: amid all this branding and spectacle, are we losing sight of what a fair and functioning state should be?

Returning to Debord, he didn’t call his theory The Society of the Spectacle for nothing. He talked about a troubling divide in our collective society. Debord warned that in a society dominated by spectacle, images, and superficiality, the true meaning of social relationships can be lost — not because people naturally lack empathy. In such a society, we’re just no longer encouraged to cultivate empathy or understanding for one another but instead are bombarded by slogans, opposing sides, and a constant stream of brands competing for our attention.

Where politicians once acted as representatives of the people, focused on serving the common good, their role now shifts to that of individual brands fighting to survive in the public arena. We have entered an era in which political figures are profiled as brands, and products to be sold, leading to the marginalization of fundamental issues, human values, and genuine engagement. This commercialization of politics shrinks the space for authentic human connection and understanding, which are essential for a healthy society. Empathy—the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes—becomes increasingly rare as the focus shifts to personal branding and self-promotion.

In such a world, we’re less inclined to listen to the real problems of others and more likely to ignore those stories or even use them as PR material. This shift threatens to erode the foundation of solidarity and understanding in society, making us less willing to work toward collective solutions.

This loss of empathy and connection is concerning not only for the present but also for the future, as society becomes increasingly fragmented by superficial impressions, image-building, and personal brands—at the cost of a genuine social fabric and real care for one another.

Your voice. Your freedom?

"Your voice, your freedom." It’s a strong statement—one that carries great significance, especially in places where freedom of speech is not a given. In many countries, people are censored when expressing their thoughts. In some, the internet is controlled by the government, dictating what citizens can see and share. The choice is no longer theirs. But isn’t that becoming true for all of us in some way? Tech companies and social platforms subtly shape our online experiences, often guiding what we see, think, and share.

Within this context, your voice, your freedom represents an important ideal. But what happens when a social media platform adopts this phrase as its core philosophy? TruthSocial.com presents itself as “America's 'Big Tent' social media platform that encourages an open, free, and honest global conversation without discrimination…”42 A bold claim.

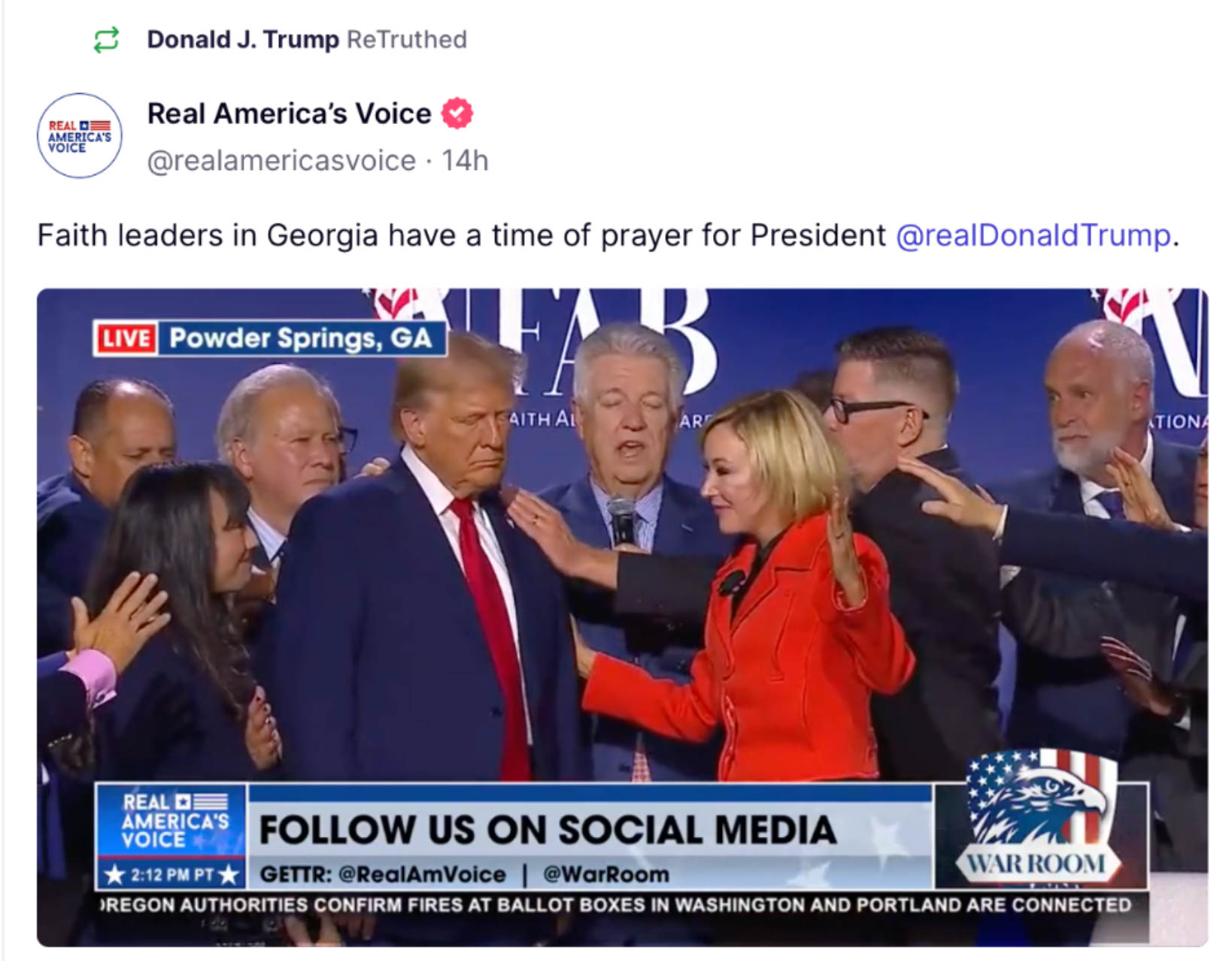

Okay so, a quick look at the platform, it takes less than a minute to land on Donald Trump’s profile. That’s hardly surprising, given that Truth Social was launched by Trump’s media & technology group after he was banned from Twitter and Facebook for spreading misinformation, hate speech, and violent rhetoric.

The platform itself bears a striking resemblance to X, where Trump is now welcome again after a year of banishment. Still, intrigued by the platform's name Truth Social, and Trump’s reputation for bending the truth, I visited his profile. The first things I noticed:

- A repost of Elon Musk sharing what looked like a political pamphlet disguised as a meme.

- A tweet with two WOWs, seven exclamation marks, and three question marks in a row.

- A video of famous faith leaders in Georgia praying for Trump and his presidency which seems more like a carefully constructed moment of woreship than a church service.

It is interesting to think social media platforms present themselves as spaces for self-expression and freedom of speech, yet they actively shape and restrict what we see. TikTok, for example, has been known to suppress posts from LGBTQ+ users, disabled individuals, and those who don’t fit conventional beauty standards—claiming it’s to "reduce bullying." In reality, it erases people’s voices and visibility who do not fit into the mainstream desirability. Instagram, too, recently placed posts about trans experiences under the label of "sensitive content," while simultaneously loosening fact-checking measures, creating more space for misinformation and discrimination.43

These digital exclusions mirror broader political structures. In January 2025, Trump signed an order restricting the U.S. government’s recognition of gender to only male and female, effectively erasing legal acknowledgment of trans identities.44/sup> His rhetoric aligned closely with right-wing movements in Europe and Latin America, showing how these exclusionary ideologies spread across borders, amplified by media and spectacle. The same mechanisms that dictate what we see on social platforms also reinforce who is granted visibility and legitimacy in society.

Trump: The Kim K of politics

Trump is often discussed as a politician, businessman, or media personality—but above all, he is a brand. He has mastered the art of self-branding in a way few others have, extending his influence from the corporate world to the highest political office.

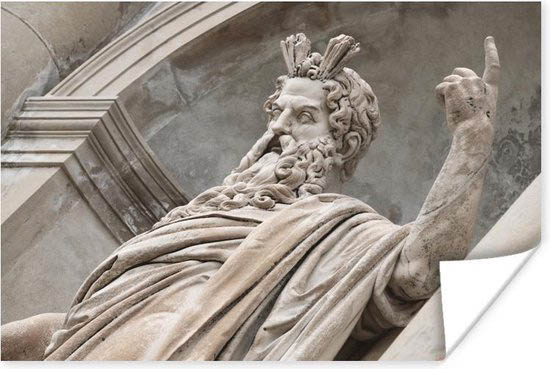

Even after the recent assassination attempt, Trump rose like a prophet—his fist in the air, security surrounding him. As he was helped to his feet, he took a deliberate moment to hold up his fist, showing defiance.

I can’t help but compare this image to famous historical statues. Take Julius Caesar, immortalized in sculptures where he raises his arm—a ruler synonymous with power and ruthlessness. Zeus, the most dominant god in Greek mythology, is often depicted holding his thunderbolt in the air. Or even Peter the Great, the name says enough right, on his horse with his arm rising.

It fascinates me that even after such a shocking event, Trump instinctively turned it into a profitable moment. His ability to use iconography, whether consciously or not, is remarkable. That moment—Trump standing with his fist raised, security surrounding him—became instantly iconic. It illustrates his ability to transform even a moment of crisis into a symbol of resilience and strength.

It is also worth considering the recent online trend where men across the U.S. and Europe frequently reference the Roman Empire. Whether consciously or not, that imagery may have influenced Trump’s instinctive reaction—or perhaps it influenced mine in drawing the parallel.

One thing is certain: by associating himself with divine and historical figures, Trump taps into deeply rooted ideas of masculinity and authority. The Roman Empire, often framed through war, politics, and elite power, carries strong connotations of dominance and leadership. Whether by strategy or coincidence, Trump continues to position himself within this visual narrative—turning politics into spectacle and reinforcing his brand of power.

This brings me back to my original question

How do online platforms and the commodification of communication shape the way young adults and teenagers engage with each other & with politics? Trump’s presence—both online and offline —is enormous, and his influence extends far beyond traditional politics. I wrote this chapter two weeks ago (Febuary 2025), and since then, he has officially declared that the state will only recognize two genders and plastic straws are back. (Apologies for the not-so-in-depth shortcut—I just haven’t been able to keep up with all the changes Trump has made lately and I have a deadline…) This is how these shifts happen: first, there is talk. Then, policies start to shift. And over time, ideas that once seemed extreme begin to feel like part of the norm.

But this is not just a political statement—it has real, material consequences. Policies like this increase the marginalization of trans and non-binary people, reinforcing discrimination in healthcare, education, and legal recognition. It fuels a culture where safety and basic rights become increasingly uncertain. And when the state legitimizes these ideas, it emboldens those who already seek to exclude, control, or harm. This isn’t just about policy shifts; it’s about the tangible impact they have on people’s lives.

Looking at the historical patterns of rising far-right movements, it’s clear that rhetoric The art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the exploitation of figures of speech and other compositional techniques. alone is never just rhetoric. Trump’s ability to market himself—especially alongside figures like Elon Musk—plays a significant role in shaping public discourse. Written or spoken communication or debate Their influence extends beyond their direct actions; they set the tone for what is acceptable, what is debatable, and what is inevitable. It’s not just about politics; it’s about culture, visibility, and power. His branding is relentless, and whether intentional or not, it continues to push the boundaries of what is normalized.

If we’ve learned anything from history, it’s that these shifts don’t happen overnight, but once they do, they’re hard to undo. What starts as a spectacle can quickly become policy, and what begins as rhetoric can reshape reality.

Conclusion

Why does all of this matter to me? Because I love images—visuals, photographs, film—everything that speaks in a language beyond words. Images show what we long for, what we fear, and what we sometimes struggle to put into words. It’s through imagery that I make sense of the world.

It still amazes me that you can capture beauty—or the depth of your imagination—without needing to explain it. Like music, images can connect us to something bigger. Maybe that’s why I wrote this research paper: to better understand the forces that sometimes pull me away from that connection, and to find ways to hold onto it.

Because, as Guy Debord describes, living inside the spectacle can feel overwhelming. The constant flood of images and performances can make it hard to tell what’s real and what really matters. In a world that constantly asks us to consume, produce, and move faster, it feels important to slow down and question where we put our attention. To ask where the images we encounter come from—and what their purpose is. To sell? To inform? To entertain? To guide? Or simply to exist?

If we never pause—if we keep scrolling, posting, watching—it becomes easy to detach from the people and places around us. Easy to lose track of what actually matters. For me, making images, paying attention to my surroundings, helps break that cycle. It reminds me to actually see, not just look. It’s a way of staying present.

Maybe that’s what it comes down to: learning to step back once in a while. To pay closer attention. Not just to images, but to each other—online and offline. Because if we don’t, it’s easy to lose track of what’s right in front of us.